The first appearances of coding agents were within our editors, as a natural progression from tab autocompletion. When Claude Code was released, almost a year ago, it innovated in many ways, particularly by demonstrating that although we write almost all of our code in editors, the agents themselves don’t have to be constrained to IDEs. As a result, most of our agentic development moved to the terminal.

With the release of the Codex App, we will start to see a push towards richer interfaces. However, this raises the question: if we can run coding agents anywhere, where is the best place to run them?

Case study: Tidewave for full-stack web development

In this section, I will talk about Tidewave, the coding agent we built for full-stack web development. It is a sales pitch but I hope it is a good example of what we can gain by building vertical coding agents.

Tidewave was born out of frustration when using coding agents to build web applications. I frequently stumbled upon scenarios such as:

-

The agent would tell me a feature was complete, but when I tried it in the browser, form submission would not complete

-

Whenever I encountered an exception page during development, I had to copy and paste stacktraces from the browser to the agent

-

I had to constantly translate what was on the page to source code. If I wanted to “Add an Export to CSV button to a dropdown button”, the first step was typically to find where the template or component the dropdown was defined in

Ultimately, because the coding agent was unable to interact with or see what it produced, I had to act as the middleman:

And while things have improved within the last year, most of the tooling out there does not fully close this gap. For example, while coding agents can read logs and editors like Cursor do include a browser, they do not correlate the browser actions with the logs, leaving space for guess work and context bloat. Or when the browser renders a page, it doesn’t know which controller or template it came from.

We solved this problem by moving the coding agent to the browser and making it aware of your web app:

-

You open up Tidewave in your favorite browser and its agent can now interact with the page you are looking at, validating the application works as desired by accessing the DOM, loading pages, filling forms, etc

-

When something goes wrong, we parse and feed the exact information from the rendered error page. We also include any

console.logand server logs related to the particular agent action (instead of the whole history) -

When you inspect an element in Tidewave, we automatically map DOM elements to source files. If you inspect a dropdown, we tell the agent its location on the page as well as the template/component it came from in the source code

-

The coding agent has access to your backend too, so it can read documentation, execute SQL queries, and even gets a REPL-like environment. So when the agent gets stuck, it can navigate the data, run code, and explore APIs, like any developer would

More importantly, this is all implemented by connecting the agent to your running application. You can ask your agent to analyze cache usage in your Rails application or to debug a LiveView in Phoenix, and it can do so because they talk to each other directly. Your agent is no longer limited to a series of bash commands.

Overall, the agent becomes more capable, and we no longer need to act as the middleman:

For all of the above to work, instead of building a generic agent that works with every tool, Tidewave directly integrates with each web framework we support (Django, FastAPI, Flask, Next.js, Phoenix, Rails, and TanStack Start), mapping all layers to the agent, from the database to UI.

And that’s what I mean by vertical integration: coding agents become integrated into the specific platform or runtime they’re building for. They understand the relationship between code and its live behavior, and can debug both.

Vertical integration everywhere

We can easily draw parallels between the above and other domains. Agents for mobile development must have full access to a simulator to interact with the app UI, translate view hierarchies to source code, and monitor network requests. Similar patterns could apply to IoT devices, game development, etc.

As a matter of fact, this isn’t even a new idea. Data scientists were the first to embed agents directly into their notebooks, where they can execute code, visualize results, inspect dataframes, etc. They were the first to realize the benefit of vertically integrating agents and everyone else is just late to the party.

But how can we make these vertical integrations possible? If we want agents to access our runtimes and environments, could MCPs be the tool to make this a reality? That’s what we originally thought…

MCPs are not the answer

Tidewave was first prototyped as a Model Context Protocol (MCP) server and it quickly became obvious it wasn’t enough. In this section, I’ll focus on how MCPs can be detrimental to user experience. In particular, we’ll look at its limitations as a pull-only interface and its text-based constraints.

Pull-only interfaces

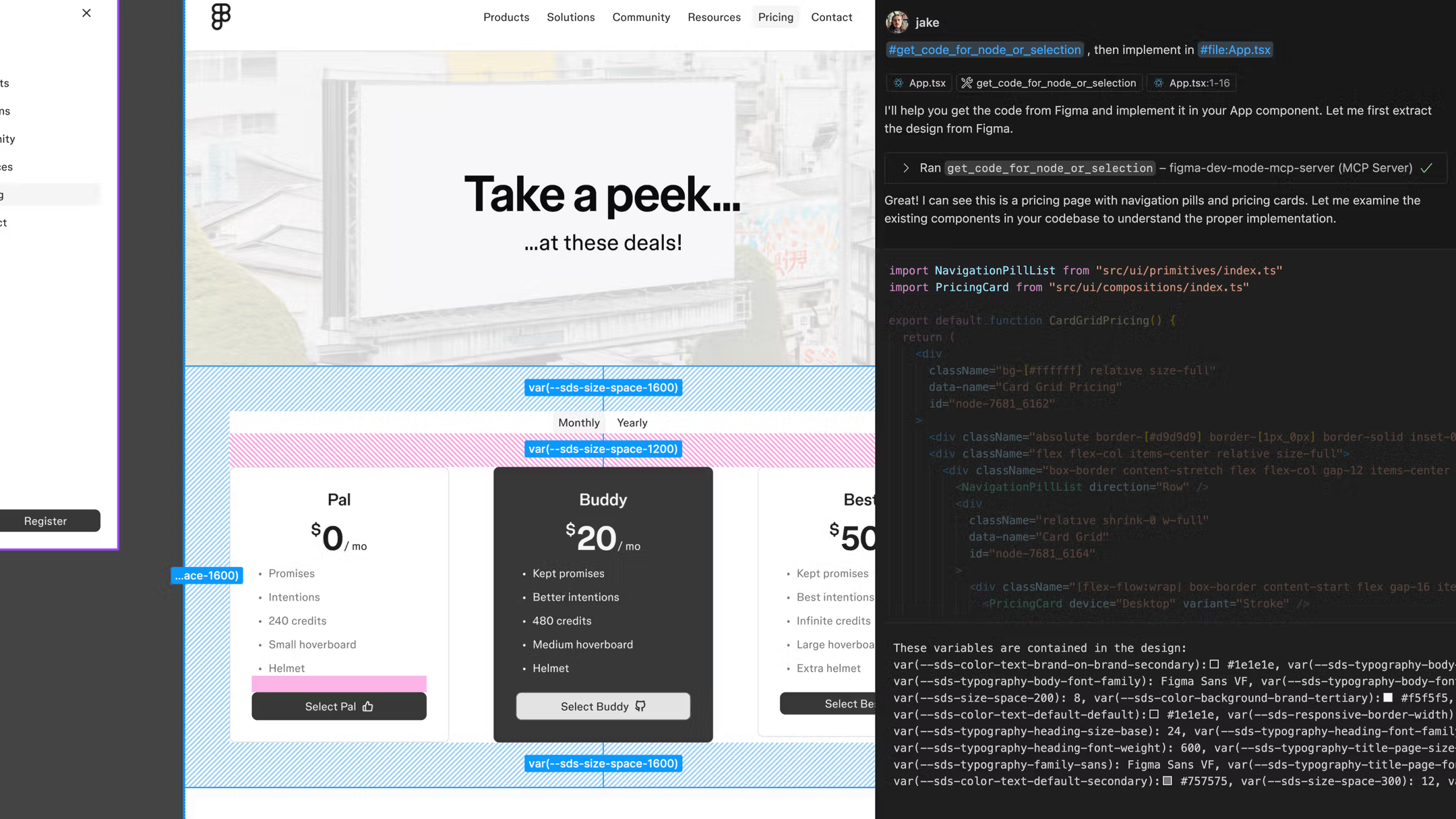

As an example, let’s look at Figma’s MCP. It allows developers to select an element in Figma’s desktop app and ask the agent to implement the design. Here’s a screenshot from their announcement:

As you can see, you’re required to make a selection in Figma, then explicitly ask the agent to query your selection. The agent then proceeds to talk to Figma and get the relevant data. That’s a lot of unecessary back and forth! If I already selected an element on Figma, it should take a single click to embed that information into my prompt.

Now imagine if, every time I inspected an element in the browser, we had to tell the agent to ask the browser about the selection. We refused to implement that. Instead, we made it just work:

Furthermore, by making the inspected elements part of our prompt, you can select multiple elements and dictate how they all need to change at once. You can reorder, swap, and coordinate multiple changes easily.

Similarly, when you see an error page in the browser, you should only need to click a button to fix it - not copy and paste stacktraces or ask the agent to read logs.

None of this could be built with MCPs because they are pull-based. The agent decides when to invoke the MCP and you are forced to ask the agents to perform actions on your behalf. MCPs do not allow us to attach rich metadata to prompts either.

Text-based constraints

Imagine you need help addressing comments in a pull request. You can tell the agent to use GitHub’s MCP or even use a custom skill that uses GitHub’s CLI to fetch all current comments. But once the agent does its initial assessment, all further exchanges happens through text: “ignore this comment”, “no, not this comment, the one above it”.

Now compare that to using any graphical (or even a terminal) interface: we can reply in thread, comment on specific lines, or click a button to dismiss invalid feedback altogether. In other words, when we put our integrations behind MCPs, all exchange happens on text, and we often end-up with worse user experiences.

Instead, our goal is to build agentic tools and user experiences side-by-side. For example, when we added Web Accessibility diagnostics to Tidewave, we exposed additional tools to the agent, but we also provided a polished experience for when developers want to remain in the loop:

Our recently announced Supabase integration works the same: it runs performance and security advisors on your database and present them to you. If you want to dig deeper, you can do it all through a rich interface. And if you don’t care about any of that, you can either click the “Fix all” button or ask your agent to do it for you.

To build these experiences, we had to invert the control. We don’t want the agent to call us, we want our tools to call the agent.

Agent Client Protocol (ACP) to the rescue

Say you want to build your own agentic loop, up until recently, doing so meant to:

- Integrate with one or more providers (Anthropic, OpenAI, etc)

- Craft and refine instructions to guide models (prompt engineering)

- Write fine-tuned tools for reading, searching, writing, and executing code

- Explore and implement context engineering techniques

While the above is already a lot of work, you must remember that prompt engineering, tool calls, etc. must be fine-tuned per model. For example, when OpenAI announced GPT-5-Codex, integrators had to write new prompts and new tools, even if they already supported GPT-5.

And the above covers only the basic loop! What about AGENTS.md, MCPs, or skills? And you haven’t even started working on what makes your coding agent unique.

Luckily for us, many of the leading AI companies have built their own coding agents (Claude Code, Codex, Gemini CLI) tailored to their models, and many have exposed those agents through SDKs. We also have fantastic open source alternatives. This means you can cut out much of the work above, but, if you want to support multiple providers, you’re still on the hook for integrating them one by one.

That’s exactly where the Agent Client Protocol from the Zed team comes in. It standardizes communication with coding agents, so you implement one protocol and support multiple agents at once. This ultimately allows you to focus on the runtime integrations and user experiences that make your coding agent unique.

Furthermore, even if you’re not implementing your own agent, ACP should matter to you because it brings portability to developers. You can use a single coding agent across the terminal, your editor, and Tidewave, reusing the same settings for hooks, skills, and subagents. And perhaps more importantly, the same subscription.

We are big fans of the Agent Client Protocol and we are excited to build on top of it alongside companies like Zed and JetBrains.

Summary

Generic agents that work everywhere force awkward workflows where we constantly act as a middleman. Instead, we want to embed agents into the platforms we are building on, so they can see the relationship between code and behavior, interact with live apps, and debug in real-time.

However, to build these rich experiences, we need to invert the control and own the agentic loop. The Agent Client Protocol (ACP) allows us to do so by standardizing communication across providers, so we can focus on the user experiences and integrations that make our coding agents unique, instead of wrestling with multiple SDKs.

I hope this article inspires you to fine-tune your own coding agents and, if you are looking for a coding agent tailored to full-stack web development, give Tidewave a try!